French Heritage Day

French Heritage Day is usually held on the first Friday in November in concert with National French Week, sponsored by the American Association of Teachers of French. This year, because of field trip restrictions, we will be moving French Heritage Day to Saturday, November 7 and inviting students and teachers to visit the fort with their families. Guests will experience many of the same engaging programs that we have offered on French Day Friday in the past. All guests are asked to wear a mask and practise social distancing! Old Fort Niagara is a large site and many of the activities will be outdoors.

French Heritage Day is usually held on the first Friday in November in concert with National French Week, sponsored by the American Association of Teachers of French. This year, because of field trip restrictions, we will be moving French Heritage Day to Saturday, November 7 and inviting students and teachers to visit the fort with their families. Guests will experience many of the same engaging programs that we have offered on French Day Friday in the past. All guests are asked to wear a mask and practise social distancing! Old Fort Niagara is a large site and many of the activities will be outdoors.

French Heritage Day at Old Fort Niagara offers students and their families a variety of experiences that will help them better understand the early French exploration and occupation of the Great Lakes region during the 17th and 18th centuries. The day’s program includes living history programs about garrison life, trade, architecture, music, travel, foodways, Native-American relationships and other topics.

Cost: Admission to the program is discounted at $14.00 for an adult and $9.00 per student (please show school ID). Tickets are available at the door.

Safety Guidelines: Please wear a face covering and practice social distancing. Our list of safety precautions is available at https://www.oldfortniagara.org/visitor-information

Directions: From Niagara Falls, NY, take I-190 North to Exit 25B. Follow signs to the Niagara Scenic Parkway North/Fort Niagara. Follow the Niagara Scenic Parkway North to Fort Niagara State Park, North Entrance. Once inside the park, follow the signs to Old Fort Niagara. Park in the large public parking area adjacent to the Fort Niagara lighthouse. Lost? Call (716) 745-7611.

Pre-visit video (in French) here -

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uqKMGMPGoAo&list=TLPQMDExMDIwMjDNzJwqMhN9qg&index=1

Pre-visit Readings

The Garrison

Soldiers stationed at the Fort were known as the Fort's garrison (la garnison). Their duty was to guard the fort and defend it in case of attack. They also helped construct new buildings and fortifications and made repairs to the fort as needed. Sometimes soldiers were detached to garrison other nearby posts or to escort supplies and trade goods along the portage road from Fort Niagara to the upper landing above Niagara Falls.

Fort Niagara's garrisons came from several different military organizations. For most of the Fort's history, garrisons were drawn from Les compagnies franches de la Marine, independent companies of the Navy. This organization was created by King Louis XIV to protect France's overseas colonies.

During the final years of French occupation of Fort Niagara, regular army troops from metropolitan France served in the garrison. Soldiers from the regiments Guyenne, Bearn, Royal Roussillon, and La Sarre served at the Fort during the French and Indian War (1754-1760).

Enlisted soldiers mostly came from France. They were supposed to be at least 16 years old and 5' 6” tall. Terms of enlistment varied from six years to life. Soldiers were paid 9 livres per month (each worth about $14.00 in modern money). Deductions for uniforms, food and medical care meant that common soldiers received but a fraction of their pay.

Once a soldier enlisted, he received his nom de guerre, a nickname that came to supplant his real name. A soldier's nom de guerre was usually based upon his background or a personal characteristic.

During the summer campaign season, militiamen (milicien) also served at the Fort. In New France, most able-bodied men between the ages of 16-60 served in their parish militia. They helped move supplies to French posts in the upper country (pays d'en haut) and accompanied raids against Anglo-American settlements.

The Soldiers' Day

Soldiers rose at dawn, dressed, cleaned the barracks and then prepared breakfast.They then received the orders of the day from the Sergeant around 7:00 am. From here they could be assigned to guard duty, the manual exercise, or to fatigue duties. If not assigned, they had free time. They ate dinner around noon and supper between 5:00 and 7:00 pm. At sunset, drummers beat tattoo and soldiers retreated to their barracks.

Soldiers rose at dawn, dressed, cleaned the barracks and then prepared breakfast.They then received the orders of the day from the Sergeant around 7:00 am. From here they could be assigned to guard duty, the manual exercise, or to fatigue duties. If not assigned, they had free time. They ate dinner around noon and supper between 5:00 and 7:00 pm. At sunset, drummers beat tattoo and soldiers retreated to their barracks.

Soldiers assigned to guard duty reported to the Guard Room at Noon and served a 24-hour shift. During this time, they could rest or cook a meal but they had to remain in uniform at the ready. Every two hours the guard made the rounds of the fort to post new sentries.

Clothing

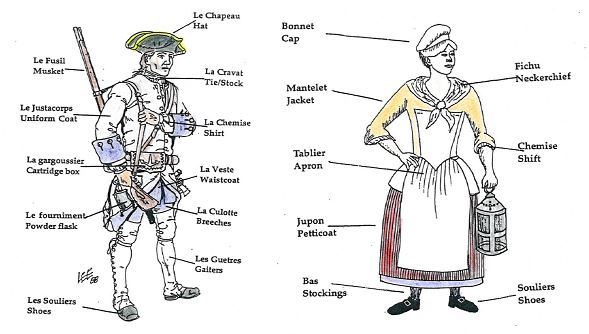

Soldiers were issued a military uniform that consisted of a wool coat (justacorps), sleeved woolen waistcoat (veste), breeches (culotte), Shirt (chemise), gaiters (guetres), shoes (souliers) and hat (chapeau). Soldiers often substituted articles of Canadian dress (habliment canadien) because it was more practical in a wilderness environment. These included Indian leggings (mitasses), breechclout (brayet), hooded coat (capot) and knit cap (tuque).

Women’s dress varied according to means and social status. Upper class women from Quebec or Montreal could afford to wear the latest gowns from France. Working class women dressed more modestly and practically for doing manual labor. Below are illustrations of a common soldier and working class woman of New France.

Women and Children at the Fort

As a military post, most of Fort Niagara's residents were men. There were however instances when women and children lived at the Fort. Unfortunately, the women and children who stayed at the Fort during the French era are poorly documented. There are exceptions however.

In 1752, the Fort's Commandant, Captain Claude-Pierre Pecaudy de Contrecoeur brought his wife of 23 years, Marie-Madeleine, and his two young daughters to live with him in the French Castle. During the siege of 1759, another officer's wife, Madame Douville took refuge at Fort Niagara and organized the women of the garrison to sew sandbags for the Fort's defense. When Fort Niagara surrendered to the British, it was noted that among 600 defenders were about 24 women and children. Women's roles in an 18th century garrison were largely to provide laundry services and serve as nurses.

Native women also frequented the Fort. During military campaigns involving Native allies, warriors' dependents often remained at the Fort for subsistence, while male family members fought alongside the French in far-off campaigns.

Food

Even in the 18th century, French cuisine was noted for its distinctive character. The artful preparation of sauces, liberal use of wine and herbs, and quality confections and pastries set French cuisine apart from the foods of other countries.

In New France, especially in the pays d'en haut, cooks often lacked key ingredients, equipment and time to prepare such fare. Travelers did comment, however, that the common person's diet in the colony was superior to that of France. In particular, colonists were able to eat much more meat and white flour than their metropolitan cousins.

The soldier's basic diet was a monotonous ration of salt pork, bread, and peas. A soldier's ration consisted of 1 ½ pounds of bread, 4 oz. of pork or 8 oz. of beef, 4 oz. of peas, ½ oz. of butter and 2.6 oz. of molasses per day. This diet provided only about 2,000 calories daily, when 2,550 to 3,000 calories per day were needed for basic sustenance. Officers received this basic ration, but with the addition of wine, brandy, a ham or sheep, and jar of vinegar, they enjoyed more and tastier fare.

To augment their diets, soldiers hunted wild game, fished, and raised vegetables in gardens located across the Niagara River in what is now Ontario. At Niagara, soldiers ate berries, nuts, cod, eel, rabbit, bear, venison, geese, and duck.

Peter Kalm, a Swedish scientist visiting in August 1750 noted: Both Indians a nd resident French soldiers from Fort Niagara are said to appear [at Niagara Falls] daily...to gather the [killed] supply of sea fowls. The commandant of the Fort Niagara...assured me that the soldiers there lived in the Autumn a long time principally from the birds found dead beneath the falls, which they prepared for food in various ways.

nd resident French soldiers from Fort Niagara are said to appear [at Niagara Falls] daily...to gather the [killed] supply of sea fowls. The commandant of the Fort Niagara...assured me that the soldiers there lived in the Autumn a long time principally from the birds found dead beneath the falls, which they prepared for food in various ways.

Cooking in the 18th century, without our modern stoves and microwaves, was a laborious process. First the fire had to be properly built (without matches or lighters). Water had to be carried. Cooks had to manipulate heavy cast iron stew pots in and out of the hearth with the constant danger of burns and catching fire.

At Fort Niagara, soldiers cooked their meals in the barracks room fireplace. Seven men comprised a mess (plat): a group who cooked and ate together. Each mess was generally issued a cook pot and 7 spoons. Professional bakers prepared the bread in La Boulangerie. Bread was issued to the troops every four days.

Shelter

French architecture on the Great Lakes was derived from French traditions but made greater use of readily available timber resources. French buildings in the pays d'en haut included military structures, trading storehouses, religious missions, civilian homes and outbuildings.

The most sophisticated building west of Montreal was Fort Niagara's Maison à Machicoulis, today known as the French Castle. The Castle's design was largely determined by political considerations. The Seneca Nation, who inhabited the area, strongly objected to the construction of a stone fort on their land. The French employed a subterfuge designing the Maison à Machicoulis to resemble a house or barracks building. They told the Iroquois that the building was a “House of Peace,” a place they could trade and negotiate with representatives of their French Father Onontio (The Governor of New France). In reality, the “House” was a well-defended fort, capable of housing some 40 soldiers.

Most structures in the pays d'en haut were much smaller and simpler than the French Castle, employing readily available timber as the building material. These included piece upon piece (piece-sur-piece), posts in earth (poteaux en terre) and half-timbered (columbage) construction.

Many of the French buildings at Fort Niagara that no longer survive were of wooden or log construction. In addition to the French buildings that remain today (the Castle and the Powder Magazine) there were some 22 wooden buildings scattered around the Fort’s interior.

Artisans

Construction at Fort Niagara required numerous skilled artisans. Carpenters, cabinet makers, blacksmiths, and stone masons all worked on the buildings at the Fort. Wheelwrights were also in demand to build and maintain carts used on the portage road around Niagara Falls.

Construction at Fort Niagara required numerous skilled artisans. Carpenters, cabinet makers, blacksmiths, and stone masons all worked on the buildings at the Fort. Wheelwrights were also in demand to build and maintain carts used on the portage road around Niagara Falls.

The Fort was equipped with a blacksmith shop (Le Forgeron) where iron goods could be manufactured and repaired. Blacksmiths also make simple repairs to firearms, but more complicated work was done by highly skilled armorers (armuriers). The French often provided the skills of a blacksmith free of charge to their Native allies. Necessary tools and equipment for a blacksmith included a bellows (souffler), tongs (tenailles), an anvil (enclume), and hammer (marteau).

Skilled workmen were often civilian employees but there were sometimes soldiers in the ranks who possessed specialized skills. Captain Beaujeu was not impressed with the skills of Fort Niagara's soldiers when he wrote: I do not have a man capable of making a peg...I would be satisfied with men who know how to handle an ax..So thus I cannot repair anything...”

For the most part, soldiers provided the heavy manual labor needed in construction. During the winter of 1755-56, soldiers from the Regiment de Guyenne constructed massive earthen walls that protected the Fort from artillery fire.

Fortifications

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the French were regarded as masters of military engineering. This is not surprising given the fact that France had long frontiers to protect from enemies like England, Holland and the Holy Roman Empire. France’s most famous military engineer was Sebastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707). During his long career, Vauban constructed or modified more than 100 fortresses along France’s borders.

Vauban’s principles were imported to North America, although they were often simplified to match frontier conditions. When Fort Niagara was expanded and refortified between 1755 and 1757, the principles of Vauban were employed. Hallmarks of these principles included geometrically precise earthen outer works and the use of projections called half-bastions at the Fort’s corners. These architectural elements protected the Fort’s garrison from incoming artillery and musket fire. They also exposed attackers to numerous physical barriers that could be raked with fire from multiple sides.

Defense

In addition to the Fort’s walls, ditches and stockades, soldiers relied upon their  weapons to defend the post. Soldiers were equipped with single-shot, smoothbore muskets (fusils) that operated with a flintlock mechanism and were loaded from the muzzle using a rammer (baguette). Loading and firing a single shot required 15 steps that a skilled veteran could perform in about 15-20 seconds.

weapons to defend the post. Soldiers were equipped with single-shot, smoothbore muskets (fusils) that operated with a flintlock mechanism and were loaded from the muzzle using a rammer (baguette). Loading and firing a single shot required 15 steps that a skilled veteran could perform in about 15-20 seconds.

The Fort was also equipped with artillery. By the end of the French occupation, ther e were 43 cannons (canon) and 2 small mortars (mortier) at Fort Niagara. Cannons fired solid iron balls in a relatively flat trajectory. Mortars fired exploding iron bombs in a high arc. Cannons were useful for battering down walls or firing on bodies of troops. Mortars were used to lob exploding bombs over a Fort’s wall.

e were 43 cannons (canon) and 2 small mortars (mortier) at Fort Niagara. Cannons fired solid iron balls in a relatively flat trajectory. Mortars fired exploding iron bombs in a high arc. Cannons were useful for battering down walls or firing on bodies of troops. Mortars were used to lob exploding bombs over a Fort’s wall.

Commands for Loading and Firing a Musket

Portez le fusil- Shoulder your firelock

Chargez le fusil- Prime and load

Haut le fusil- Poise Firelock

Appretez le fusil- Make Ready

En Joue- Present

Feu- Fire

Reposez vous sur vos fusil- Order firelock.

Commands for manuvers:

En avante marche- To the front march.

A droite – Right face.

A gauche – Left face.

Demi tour a droite – Right about face.

Halt – halt

Quarts de conversion a droite/gauche –

Wheel right/left.

Trade and Commerce

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the fur trade was the most important commercial enterprise in the Great Lakes region. Native peoples living throughout the upper Great Lakes hunted fur-bearing animals to trade with French and British merchants for goods manufactured in Europe. The beaver (castor) was the most popular because its fine under fur was used to make felt for hats favored by wealthy Europeans. Natives also hunted and traded deer skins, bear skins, otter, raccoon and marten.

By the 18th century, Native peoples had become quite dependent on European goods. They much preferred European firearms to the bow and spear and European clothing and blankets were much in demand. Iron tools and weapons had replaced implements made from stone.

To facilitate transactions, French merchants had developed a complex credit system that stretched across the Atlantic. Under this system, French merchants advanced goods to merchants in Montreal. These merchants hired men (engagees) to carry the goods into the interior, to military posts and Native villages. Goods were advanced to Native people on credit and accounts were repaid when the fur harvest came in. Hunting for fur bearing animals was generally done in the winter when fur was plush, while deerskins were harvested in the late summer and fall, when the leather was most pliable.

Some Natives did not wait for the traders to arrive in their villages. Instead they traveled east to get a better price for their fur harvest. Some came to trade at Fort Niagara, where they dealt with a trade agent known as a commis. Many more slipped past the Fort to trade with the British at Oswego (150 miles east of Niagara).

Travel

In 18th century North America, the easiest travel was by water. Durin.jpg) g the spring, summer and fall, armed sailing ships brought men and military supplies across Lake Ontario from the head of the St. Lawrence River. Smaller boats called bateaus and canoes were also common on the Lake. Once these vessels reached the lower Niagara River, they had to be unloaded and cargoes carried over the portage around Niagara Falls. The 188-foot climb up the Niagara Escarpment was perhaps the most arduous part of the journey from the Atlantic Ocean to the upper Great Lakes.

g the spring, summer and fall, armed sailing ships brought men and military supplies across Lake Ontario from the head of the St. Lawrence River. Smaller boats called bateaus and canoes were also common on the Lake. Once these vessels reached the lower Niagara River, they had to be unloaded and cargoes carried over the portage around Niagara Falls. The 188-foot climb up the Niagara Escarpment was perhaps the most arduous part of the journey from the Atlantic Ocean to the upper Great Lakes.

At most portages, engagees were expected to carry two 90 pound trade bales at the same time. The height and steepness of the Niagara Escarpment and its location in Seneca territory presented special problems. At first the French hired Seneca men to carry goods on the portage. Later they improved the portage road and used carts pulled by draft animals to move goods along the portage. Daniel Chabert de Joncaire, the French officer who had charge of the portage, once described using cables to pull goods up the steep slope.

During the winter months, water navigation was cut off due to ice formations. Travelers between November and April had to use snowshoes (raquettes), ice skates (pátins a glace) and toboggans (traines) to get from one place to another. A soldier names Jolicoeur Charles Bonin left us a chilling description of his winter trek from Montreal to Fort Niagara:

We often had to cross rivers in water, where the ice was too weak to risk going upon it. This must be done by undressing and carrying the clothing on our heads, and after crossing, we had to dress again very quickly and run to warm up. This occasionally happened three times in the course of a day. We experienced this discomfort four days of our journey. Then we were compensated for it on the shore of Lake Ontario, where the ice was strong enough to hold us, and where those who could skate pulled seven or eight traines in a row, one after the other with men upon them.

Religion

French garrisons of over 40 men were to have chapels served by a military chaplain, drawn mostly from the Recollect order. Recollects were part of the Franciscan order and observed a vow of poverty. One such priest was Father Emmanuel Crespel (born 1703). Crespel joined the Recollects at age 16. In 1724 he arrived in Quebec where he studied theology and was ordained a priest in 1726. Between 1729 and 1732, Crespel served as chaplain at Fort Niagara. This is what Crespel had to say about Niagara:

I found the spot very agreeable, the chase [hunting] and fishery are productive, the forest of ext reme beauty, and full especially of walnut, chestnut, oak, elm and maple such as we never see in France. The fever soon damped the pleasure we enjoyed at Niagara and troubled us till fall set in, which dissipated the unhealthy air. We spent the winter calmly enough. I may say agreeably had not the vessel, which should have brought us supplies…been compelled to turn back…and left us under the necessity of drinking nothing but water… I learned the Iroquois and Ottawa languages, in order to converse with these people.

reme beauty, and full especially of walnut, chestnut, oak, elm and maple such as we never see in France. The fever soon damped the pleasure we enjoyed at Niagara and troubled us till fall set in, which dissipated the unhealthy air. We spent the winter calmly enough. I may say agreeably had not the vessel, which should have brought us supplies…been compelled to turn back…and left us under the necessity of drinking nothing but water… I learned the Iroquois and Ottawa languages, in order to converse with these people.

France on the Niagara Time Line

1607: Permanent French settlement established at Quebec.

1615: Samuel de Champlain explores the Ottawa River to Georgian Bay and Lake Huron.

1640s: Military expansion of the Five Nations of the Iroquois against rival Native Americans around Lake Erie. Increased hostility toward the French.

1669: Earliest documented visit of a European, Rene'-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle to the mouth of the Niagara River.

1678: Arrival at Niagara of a second expedition led by La Salle. “Discovery”of Niagara Falls by Father Louis Hennepin.

1679: La Salle establishes Fort Conti on the modern site of Fort Niagara, builds the sailing vessel, Griffon, above Niagara Falls and sails into the upper Great Lakes. Fort Conti burns by accident and is abandoned.

1687: Governor Denonville of New France attacks Seneca villages on the Genesee River. The French build Fort Denonville on the modern site of Fort Niagara. Denonville returns to Montreal leaving 100 men at Fort Denonville.

1688: Winter: Fort Denonville's garrison reduced from 100 to 12 by starvation and disease. On Good Friday friendly Natives and a relief expedition rescue Fort Denonville's survivors and re-garrison the post. In September the French abandon the Fort.

1689: Worsened relations between France and England marked by the outbreak of the War of the League of Augsburg in Europe. In America the fighting is known as King William's War. By the end of hostilities in 1697, the Iroquois have suffered badly at the hands of the French and adopt a neutral attitude in the conflict between French and British colonists.

1701: Great Peace of Montreal establishes peace between French and Iroquois. Beginning of the War of Spanish Succession in Europe. The fighting in North America is known as Queen Anne's War (1702-13). Conflict ends in 1713 with the Treaty of Utrecht which defined French and British spheres of influence in North America.

1720: Louis-Thomas Chabert de Joncaire, who has long represented French interests among the Five Nations of the Iroquois, receives permission from them to establish a trading house on the Niagara River. This is known as the Magazin Royale at the foot of the Niagara Escarpment at modern Lewiston.

1725: Chabert and other French agents obtain permission from the Five Nations to construct a stone house for trading at the mouth of the Niagara River.

1726: A French expedition arrives at the mouth of the Niagara River and begins construction of the stone house, today known as the French Castle.

1727: Work completed on the French Castle.

1739: A strong French force passes through Fort Niagara on its way from Montreal to attack Chickasaw Indians in western Tennessee.

1744: The War of Austrian Succession spreads to North America as King George's War. Fort Niagara repaired and strengthened.

1747: Fort Niagara Bake House constructed.

1748: Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle ends the War of Austrian Succession/King George's War.

1749: Fort Niagara serves as a base for a French expedition to the Ohio Valley. Led by Captain Celoron de Blainville, it is intended to establish French claims to the area.

1751: The French construct Fort du Portage at the head of the portage above Niagara Falls to prevent Natives from bypassing Fort Niagara in favor of the British post at Oswego.

1753: Fort Niagara serves as the base for a French expedition to the Ohio Valley. These troops construct forts from Lake Erie to the modern site of Pittsburgh which leads to the outbreak of a new war between the French and the British.

1754: Open conflict between the French and the British over the Ohio Valley marks the beginning of the French and Indian War.

1755: Britain and France send regular troops to North America. General William Shirley gathers an army at Oswego to capture Fort Niagara. He is unable to move against the French post. The French react by sending regular troops and Captain Pierre Pouchot to reconstruct and expand Fort Niagara.

1756: Captain Pouchot completes the new walls at Fort Niagara. War is officially declared.

1757: Pouchot completes many new buildings inside Fort Niagara, including the Powder Magazine, before leaving the post in the fall. Niagara serves as an important base for Native allies of the French as they strike against the British at Lake George and against the frontiers of Pennsylvania and Virginia.

1758: British successes in capturing Fort Duquesne on the Ohio and Fort Frontenac on Lake Ontario threaten Fort Niagara.

1759: Captain Pierre Pouchot returns to Fort Niagara to defend the fort against an anticipated British attack. In July, a British and Iroquois army of 3,400 men lands at Le Petit Marais (Four Mile Creek) and lays siege to Fort Niagara. On July 24 a French relief force from Lake Erie is decisively beaten and routed at the Battle of La Belle Famille on the site of modern Youngstown. The next day, Captain Pouchot surrenders Fort Niagara and his 600-man garrison.

1760: French forces surrender at Montreal and New France falls.

1763: Treaty of Paris ends Seven Years War. Canada given up to the British.

Vocabulary

Magasin (m) storehouse

Pays d’en haut the upper country (The Great Lakes region)

Garnison (f) garrison

Nom de guerre (m) nickname

Milice (f) militia

Boulangerie (f) bakery

Plats soldiers messes

Pièce-sur-pièce piece upon piece construction

Poteaux-en-terre posts in the earth construction

Columbage half-timbered construction

Glacis slope- refers to the outermost part of a fortification

Demi-lune half-moon- refers to a triangular shaped fortification.

Fascine a bundle of sticks used to build earthen fortifications.

Forgeron (f) forge/blacksmith shop.

Soufflet (m) bellows

Tenaille (f) tongs

Enclume (f) anvil

Marteau (m) hammer

Fusil (m) musket

Canon (m) cannon

Mortier (m) mortar

Justacorps (m) coat

Culotte (f) breeches

Castor (m) beaver

Engagee (m) voyageur, fur trade employee

Commis (m) fur trade agent

Raquette (f) snowshoe

Pátin a glace (m) ice skate

Traine (f) toboggan

Hours of Operation

January 13 through March, Open Wednesday-Sunday 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m

April 1- June 30, Open Daily 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.

July and August, Open Daily 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

September 1 - October 15, Open Daily 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.

October 16 - December 31, Open Wednesday through Sunday (Closed Mondays and Tuesdays) 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.

The fort will be open daily during Christmas week, December 26 - 31.

Closed New Year's Day, Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day.

General Admission

|

Adults: |

$20.00 |

|

Children (6 to 12 years) |

$12.00 |

|

Children (5 and under): |

FREE |

Support the Fort

Old Fort Niagara is operated by the Old Fort Niagara Association, an independent, not-for-profit organization established in 1927. We do not rely on tax dollars. Instead, the Fort is funded through a combination of admission fees, museum shop sales, and charitable contributions.

.jpg)

Newsletter Sign-Up

Keep up to date on Old Fort Niagara events and happenings! Sign up here for our e-newsletter.