That the Men be Taught to Take Good Aim: Marksmanship Training in the British Army in the 18th Century

The value of accurate fire was recognized in the 17th and early 18th centuries when period drill books recommended at least some target practice for British troops. In peacetime however, parsimonious issues of lead made practice with live ammunition difficult. Historian J. A. Houlding found that the government did not stint on gunpowder and flints but issued only 1 cwt. of shot to each battalion of foot annually. This worked out to about 2 to 4 musket balls per man per year. (Houlding p. 144) Instead of stressing marksmanship, peacetime training focused on the platoon exercise, firing blanks or “squibs.”

In 1751 the Lt. Colonel of the 8th Regiment of Foot stated that he wished the troops, "were accustomed to take aim when they present, No Recruits want it more than ours, few of them having fired or even handled Fire Arms before enlisted; the Explanation of the word “present” in the manual exercise, is very different in my Opinion from what Men shou’d do when firing at an Ennemy, this gives them a Habit of doing it wrong, and I have room to believe that the Fire of our Men is not near so considerable as it would be, were any pains taken to make them good Marks men” (Houlding, p. 280)

James Wolfe, speaking of his experiences in Scotland during and after the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745, pointed out the benefits of firing live ammunition in a 1755 letter, "Marks men are no where so necessary as in a mountainous country. Firing ball at objects teaches the soldiers to level incomparably, makes recruits steady and removes the foolish apprehension that seizes young soldiers when they first load their arms with bullets. We fire first singly, then by files, 1, 2, 3 or more, then by ranks, and lastly by platoons, and the soldiers see the effects of the shot, especially at a mark or upon the water. We shot obliquely, and in different situations or ground from heights downward and contrarywise." (Findlay p. 271)

It was during wartime that the British soldier got his chance to practice marksmanship. During the French and Indian War, Lord Loudoun issued these orders to the newly raised 60th Regiment of Foot:

"They are then to fire at marks, and in order to qualify them for service of the woods, they are to be taught to load and fire, lyeing on the ground and kneeling." (Houlding p. 375)

In the summer of 1757 (the fourth year of the French and Indian War), the Lt. Colonel of the 15th Foot reported, "We have three field days every week…7 rounds of powder and ball each every man has fired about eighty four rounds, and now load and fire Ball with as much coolness and allacrity in all the different fireings as ever you saw them fire blank powder." (Houlding p. 280)

General Jeffery Amherst ordered his army, in winter quarters in New York during the winter of 1758-59, to “practice their men at Firing Ball, so that every soldier may be accustomed to it.” (Houlding p. 366).

In the months leading up to the outbreak of the American Revolution the British commander in North America, General Thomas Gage, ordered his Boston-based army to practice marksmanship. Historian Matthew Spring points out that Gage’s men practiced almost every day. Dr. Robert Honeyman witnessed this activity. Honeyman recorded:

"I saw a regiment and the body of Marines, each by itself, firing at marks. A target being set up before each company the soldiers of the regiment stepped out singly, took aim and fired, and the firing was kept up in this manner by the whole regiment till they had all fired ten rounds." (Spring p. 81).

Captain Frederick MacKenzie, of the 23rd Regiment of Foot (Royal Welsh Fusiliers) took part in the live firings at Boston:

"The regiments are frequently practiced at firing ball at marks. Six rounds per man at each time is usually allotted for this practice. As our regiment is quartered on a wharf which projects into the harbor, and there is very considerable range without any obstruction, we have fixed figures of men as large as life, made of thin boards, on small stages, which are anchored at a proper distance from the end of the wharf, at which the men fire. Objects afloat, which move up and down with the tide, are frequently pointed out for them to fire at, and Premiums are sometimes given for the best shots, by which means some of our men have become excellent Marksmen." (MacKenzie p. 4)

General William Howe, who succeeded Gage as Commander in Chief, also advocated the value of aimed fire, "The commanding officers of corps to practice their Recruits and Drafts in firing at marks, and may, when they think it necessary, order the whole out for that purpose." (Howe/Kemble p. 298).

Thomas Simes, author of a 1768 military dictionary, suggested that new recruits should be taught to fire “with ball at the target till they can hit the object six times out of twelve, for without firing at a mark, men will not be marksmen; and without being sure to kill, soldiers are not in the best possible state of war.” (Simes p. 177).

A decade later Bennett Cuthbertson advised, "When a convenient place can be obtained for fixing up a butt (a barrel), the Companies should perform all the different firings with ball cartridges once a month, it being the true method of training soldiers to the use of arms, and forming them for whatever service they may be called to; and in order to raise an emulation in this essential part of discipline, that Company, which in the course of a day’s performance, drives the greatest number of balls each should be distinguished until the next monthly practice, by a little tuft of scarlet worsted worn above the cockade." (Cuthbertson pp. 171-172).

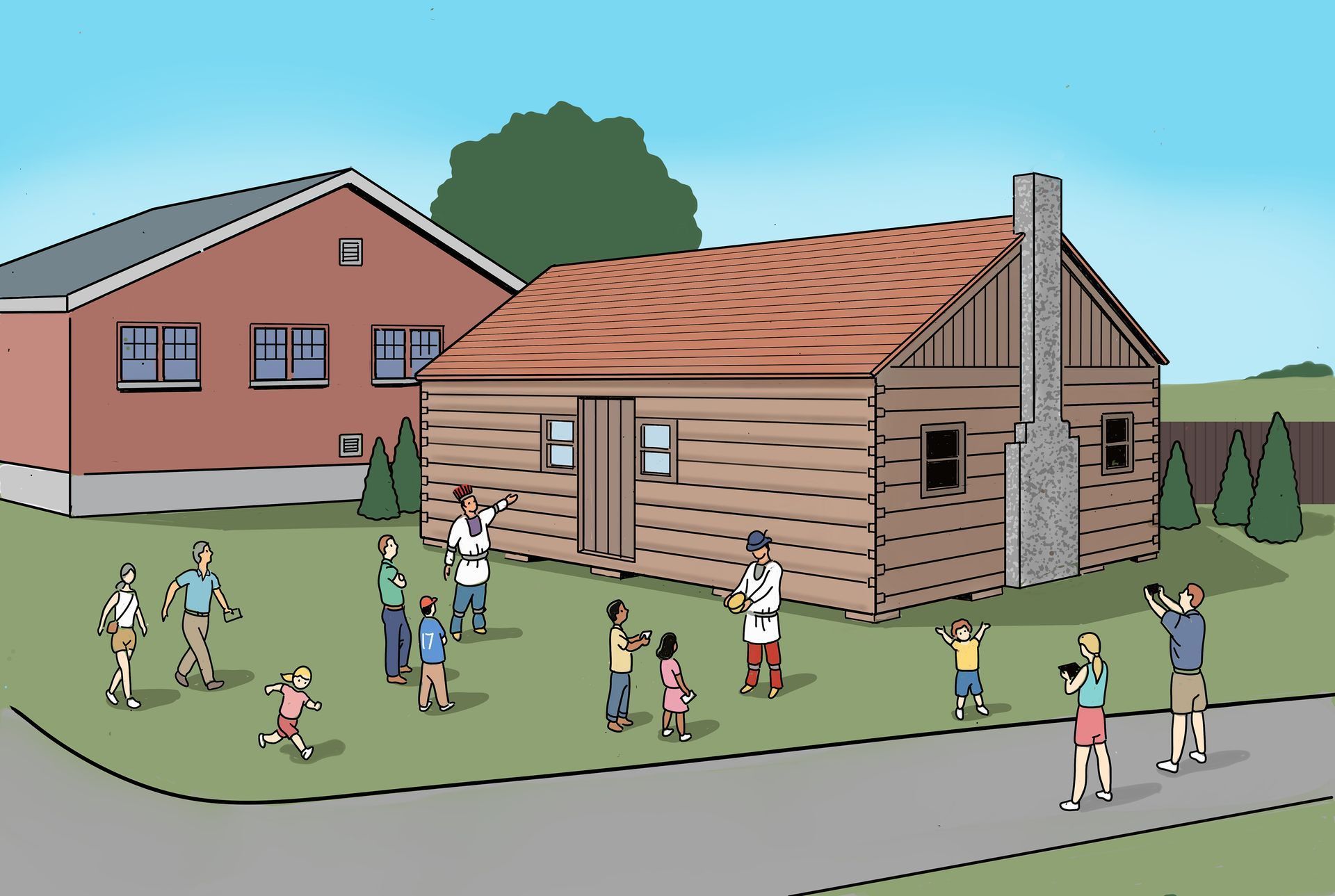

So we see it was customary during wartime for British soldiers to shoot at targets of various sorts to improve marksmanship. Such was also the case at Fort Niagara. Although recorded during peacetime, Captain Glasier’s Orderly Book from the 2nd Battalion, 60th Regiment of Foot documents several days of target training at Fort Niagara during March and April 1772. An entry for March 27 orders “Captain Stevenson’s Company to parade Tomorrow afternoon at 3 O’Clock for the Targate firing, all the men that is here of Captain Glasiers Company is to join Captain Stevenson’s.” Four days later Captain Hutcheson’s Company of the same battalion was ordered to parade for target firing. Training proceeded fairly regularly through April 1772.

Another reference to shooting at marks comes in 1780 as Fort Niagara’s commandant, Lt. Col. Mason Bolton wrote to Governor Frederick Haldimand, “The Colonel has had his men [Butler’s Rangers] out this spring (or rather winter) frequently firing at marks, &c, &c. agreeable to your Excellency’s orders.” (Haldimand Papers reel 21760 p. 278).

One would expect a unit such as Butlers Rangers to stress good marksmanship. However, aimed fire was also frequently practiced by British regulars during the French and Indian War and American Revolution. By demonstrating this for the public, Old Fort Niagara is helping to present a more accurate picture of the activities of British soldiers in America. But don’t worry, we’re only using “squibs.”

Readers can learn more about the accuracy of musket fire by visiting YouTube and watching a short video, The Effectiveness of 18th Century Musketry, on the Old Fort Niagara Association channel.

References

Cuthbertson, Captain Bennett. A System for the Compleat Interior Management and Economy of a Battalion of Infantry. Dublin: Boulter Grierson, 1776.

Findlay, J. T. Wolfe in Scotland in the ’45 and from 1749-1753. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1928.

Haldimand Papers, Reel 21670, p. 278.

Honeyman, Dr. Robert. Journal for March and April 1775. San Marino, CA: Henry E. Huntingdon Library.

Houlding, J. A. Fit for Service: The Training of the British Army, 1715-95. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981.

Howe/Kemble.The Kemble Papers1775-1783 v. 1. Collection of the New-York Historical Society. New York: New York Historical Society, 1883.

Mackenzie, Frederick. The diary of Frederick MacKenzie. 2 vols. Cambridge Mass: Harvard university Press, 1930.

Simes, Thomas. A Military Medley. London: Printed for the Author, 1777

Spring, Matthew H. With Zeal and with Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1782. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008.

Tully, Mark. The Packet II. Baraboo WI: Ballindalloch Press, 2000.