To Have the Garrison Supplied with Wood

Winter will soon be upon us and our thoughts will turn from travel and outdoor activities to hearth and home. Today most of us take central heating and a comfortable indoor temperature for granted. A flick of the thermostat is all that’s needed to keep warm during even the coldest days of winter.

Such was not the case in early America when most depended on fireplaces, warm clothing and bedding to keep warm during the winter months. According to the Farmers’ Museum in Cooperstown, the average New York farmstead consumed about 40 cords of wood in a year. This is the equivalent of about one acre of wooded land. Translating the BTUs produced by this much wood into the cost of modern heating oil yields a heating bill of around $17,000 a year. [i]

Woodcutting on the farm was the responsibility of men and boys, who spent long hard days in the woods harvesting trees for fuel. The best time to cut firewood was in the winter months when snow on the ground allowed relatively easy transport by sleigh from woodlot to dooryard . Winter was also the time when farmers had the time to lay in a store of firewood for the following year. This timetable allowed the wood to dry and season before it was needed. [ii] While cutting wood was best done during December, January and February, the arduous task of splitting and stacking was a year-round occupation.

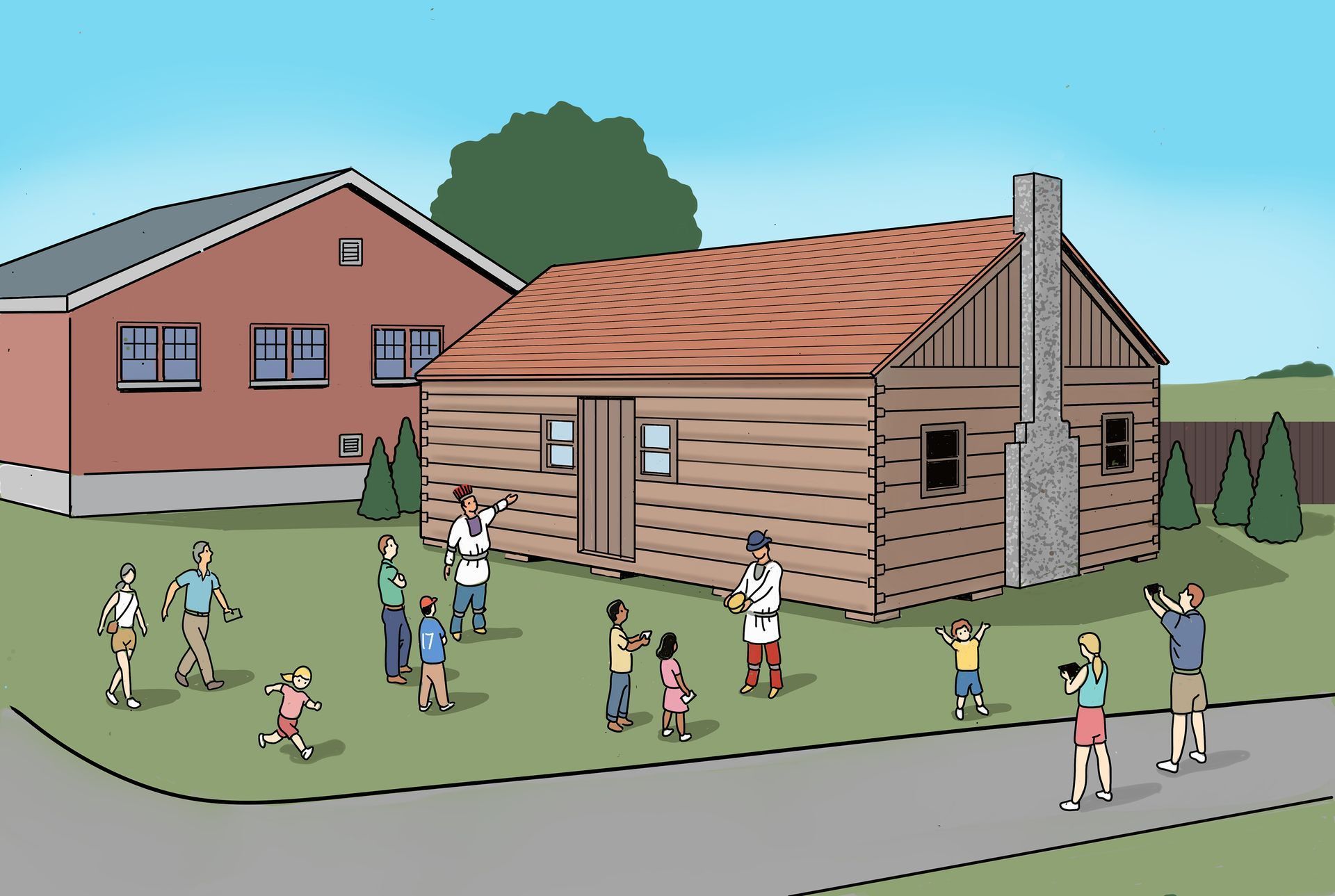

Providing firewood for a frontier military garrison intensified the challenges facing farmers. Even a reduced garrison of 30 to 40 men required a great deal of firewood for heating, cooking, baking, laundry, cleaning and hygiene. Ancillary activities like charcoal manufacture and lime burning also consumed large amounts of wood.

When Captain Daniel Hyacinthe Lienard de Beaujeu assumed command of Fort Niagara in July of 1749, he lamented to New France’s Governor, Roland-Michel Barrin de La Galissonière, “There are here no more than 50 cords of wood of the 1,200 which are consumed annually.”[iii] That means, by Beaujeu’s estimate, the Fort consumed about 30 acres of trees each year when its footprint was still relatively small.

After the British captured the Fort, Major William Walters of the 60th Regiment of Foot wrote to General Amherst “I keep the Troops constantly employed of fetching wood for the Garrison on sleighs which is good Exercise and adds greatly to their Health , as long as the frost and snow continues.” [iv] Walters continued to gather firewood through the year, writing in August 1762 that he had issued orders “… to have the garrison … supplied with wood … ” [v]

By November of 1762 General Amherst wrote to Major John Wilkins, who had replaced Walters as commandant:

Before I received your letter, Lt. Col. Eyre had shown me a copy of Lt. Demler’s report which satisfied me that the troops at Niagara had been usefully employed during the summer; but I am now to express my particular approbation of the measures which I see you had taken to preserve the health of your garrison by establishing a brewery whereby the men should be supplied with spruce beer at the easy rate of one copper a quart; and likewise of the precautions to lay in a stock of firewood, and the regulations you had made for each Mess being supplied with plenty of vegetables from their own gardens, all which must make the men live comfortably during the winter and consequently be the more fit for service when the weather will permit their being employed. [vi]

Five years later, in 1767, we find another reference to firewood in a letter from Captain Alexander Grant of the Naval Department to Booty Graves at Niagara:

You are hereby ordered and directed to take on you the command and direction of the Naval Department at Niagara, taking care to follow all orders and directions that you shall receive from time to time from Captain Brown, the commanding officer at Niagara, or myself; & all officers and seamen of the above Department are to obey you as such... firewood must be procured for Mr. McTavish in his room all winter…. You’ll always have sufficient of firewood for the people... [vii]

One of the difficulties in gathering wood resulted from the long-term military occupation of the site. Defense considerations meant that no trees stood close to the Fort. With the garrison’s voracious appetite for firewood, supplies quickly moved ever farther from the Fort’s walls. One solution to this problem was to use watercraft to move wood. On November 2, 1774 Fort Niagara’s new commandant, Lt. Col. John Caldwell, wrote to General Gage, asking for bateau to move wood from sources along the Lake Ontario shore:

I must observe that the scow when built will be so unwieldy and draw so much water that she can only be made use of on the river, for one Gale of Wind upon the Lake (from the shores of which we get our best and nearest wood) would infallibly destroy her. [viii]

Harvesting firewood could also be dangerous. In January 1814, shortly after they captured Fort Niagara from the United States, British troops left the Fort on a mission to gather firewood. After covering only about one-half mile of ground, the woodcutting party was attacked by American troops, suffering several casualties. American Major General Amos Hall reported to New York Governor Tompkins on January 13, 1814:

On the 8th inst. a detachment under the Command of General John Swift (a volunteer) and Lieut. Colonel C. Hopkins, with about 70 men, surprised a party of the British who were procuring wood about half a mile from the Fort, fired upon them, killed four of the enemy, lost one of their own men, and took eight prisoners, subsequent to which a large force of the enemy was observed to be in motion, which induced our troops on that station to fall back 4 or 5 miles to a more defensible position. The affair ended here and all is quiet. [ix]

A British account of the same incident appeared in a letter from Lt. General Gordon Drummond to Sir George Prevost:

I am concerned to report to Your Excellency a circumstance of an unpleasant nature which occurred at Fort Niagara which..may be principally attributed to the want of exertion, or…to the neglect of the commissariat in not throwing a supply of that indispensably necessary article, fuel, into that place.

A party was sent out on the morning of the 9th to cut wood, under protection of a sergeant’s covering party, was attacked by a body of the enemy, reported to consist of about 150 men, and driven in. The sergeant was severely wounded and nine men of the working party, is supposed, taken prisoners…it appears very extraordinary that any individuals of so small a fatigue party should not have been able to affect their escape, and particularly as it appears they were not furnished with arms to assist the covering party in repelling the attack or in effecting a slow and cautious retreat. [x]

Thus gathering firewood could be a mundane, arduous and even dangerous task, but one that was never far from the minds of Fort Niagara’s winter garrisons.

[i] The Farmers’ Museum: Cutting Firewood: Preparing for Winter, Part 2.

http://thefarmersmuseum.blogspot.com/2010/cutting-firewood-preparing-for-winter.html. Fireplaces were only about 10% efficient, with most of the heat going up the chimney. Stoves came into use during the 18th century but for most, the fireplace was still the most common form of heating. Peter Kalm, visiting New France in 1749 noted stoves in use, including military installations in Quebec.

[ii] See Nylander, Jane C. Our Own Snug Fireside: Images of the New England Home 1760-1860. 1993 Alfred Knopf, NY pp. 82-84.

[iii] Beaujeu to de la Galissoniere, July 7, 1749.

[iv] Walters to Amherst. Feb 2. 1761 Amherst Papers v. 21

[v] Walters to Amherst. Aug. 19, 1762 Amherst Papers v. 22

[vi] Amherst to Wilkins, November 28, 1762, Amherst Papers

[vii] Grant to Graves, Oct 23, 1767 Haldimand Papers 21678. McTavish was Simon McTavish, possibly a clerk for the Naval Department at Niagara.

[viii] Caldwell to Gage, November 2, 1774, Gage Papers, v. 124.

[ix] Major General Hall to Governor Tompkins, January 13, 1814. Documentary History of the Campaigns Upon the Niagara Frontier 1812-1814. Lundy’s Lane Historical Society, Lt. Col. E. Cruikshank, ed. v. IX p. 111. General John Swift had an interesting military career. He was born in Connecticut in 1761 and served as a private in Elmore’s Regiment during the American Revolution. Following the Revolution, he founded the town of Palmyra, NY. He reentered service at the outbreak of the War of 1812. After leading the attack on the woodcutting party outside Fort Niagara, he took part in the 1814 campaign in Canada and was killed near Fort George July 12, 1814

[x] Ibid, p. 131.